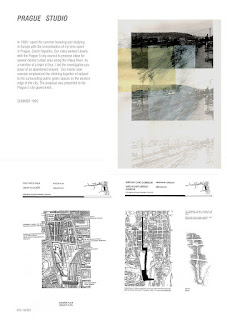

Just five years prior to 1995, Prague was still living in it's protective shell. The Czech Socialist government retreat in the late fall of 1989 still seemed so close to my summer in Prague; that summer in 1995. This was evident in a hush of silence and secrecy surrounding parts of the city and Czech life, even though my perceptional experience at the time seemed far more liberating than much of my life back in the States.

Politics can preserve a city and in the case of Prague, nearly forty-five years of self containment promoted a documentation of urban history in the making. Prague was fortunate to have escaped most of the early 20th century wars that decimated other European cities. Communism went a step further to petrify the city, keeping in tact its vibrant history while allowing selective insertions of socialist 'modern' buildings. The beauty of Prague lies in tolerance, or so it seems an acceptance of side-by-side discontinuity. Time cuts through Prague in sharp contrast. Five hundred year old villas stand next to modern department stores in casual dialogue.

Much of what Communism did in Prague, looked beyond it's central history. Rings of development creating 'accessible' housing were common at the urban fringe. Whether intentional or by virtue of available land space, development skirted the historic city center in non-invasive ways. Where new development did occur, it was selectively inserted, and as a result, preservation prevailed. The old historic city in large part remains intact. Clearly though, communism failed to successfully promote quality public space, even going so far as neglect in certain instances. Parks, monuments and streets often fell in decayed misuse and neglect under the socialist government.

Our urban planning and design class spent the summer of '95 looking at the derelict city. Unused and forgotten behind factory walls and overgrown vegetation, we imagined masterplanned scenarios for reintegration. It was a summer when boundaries dissolved.

No comments:

Post a Comment